Are autism symptoms reversible?

Reported by Lirio Sobrevinas-Covey, Ph.D.

Autism is universally described as a lifetime condition. Nevertheless, cases where persons previously diagnosed as autistic, with considerable intervention, began to exhibit normal, non-autistic behaviors later in life, have been reported. Such instances are rare, however, but its possibility hoped for by many parents and individuals with autism.

An intriguing and clinically meaningful question, therefore, is whether autism symptoms can be reversed. A recent study of mice, conducted by researchers at the Massachussetts Institute of Technology, suggests that some behavioral symptoms of autism can be reversed.

In a letter published in the journal “Nature”, the researchers report that “turning the Shank3 gene back on later in life” can reverse the key autism symptoms of problems in social interaction and repetitive behavior.

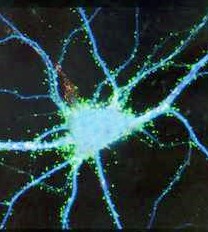

Shank3 is a protein found in many body tissues, mostly in the brain. The Shank3 gene functions dominantly in the synapses – the connections that allow the neurons to communicate with each other. Mutation of the Shank3 gene is associated with autism spectrum disorder. Mice without this gene are found to demonstrate avoidance of social interactions and repetitive behaviors.

In the mice study, the researchers engineered the samples by knocking off the Shank3 gene during their embryonic development. Then, in later life, when the mice were several months old, urning the Shank3 gene back on. The researchers found that mice with missing or defective Shank3 exhibited synaptic disruptions and autistic-like behaviors. . When the gene was turned back on, the density of the dendritic spines increased as did transmission of synaptic signals. On the behavioral level, re-expression of the Shank3 gene eliminated repetitive behavior and avoidance of social interaction. Also examined were anxiety symptoms, but these were not affected by changes in the Shank3 gene.

Many questions remain, most significantly, whether the results found in mice can be extended to humans. In showing continued neuroplasticity in diseased adult brains, the study gives hope that autism symptoms, typically first seen during childhood, can be reversed later in life.

Reference: Mei Y, Monteiro P….Feng G. "Adult restoration of Shank3 expression rescues selective autistic-like phenotypes". Nature 530 (7591): 481–4.

The Association for Adults with Autism, Philippines is a non-profit association, established by parents of individuals within the Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and professionals dedicated to the welfare of those with this developmental disorder.

The Association for Adults with Autism, Philippines is a non-profit association, established by parents of individuals within the Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and professionals dedicated to the welfare of those with this developmental disorder.